And Uphold Her Honour and Glory

By Monday P. Ekpe

Monday Philips Ekpe writes that out of the present despondency, Nigeria can rise to manifest its true worth

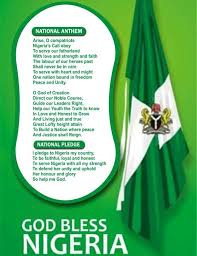

I had actually titled this piece, “The Labour of Our Heroes Past,” a line from the first stanza of the Nigerian National Anthem, but dropped it on realising that too many young citizens are so overwhelmed and disillusioned by today’s challenges – most of which they simply can’t separate from the perceived failings of the older generation – that any reminders of a romanticised past, including its recorded acts of heroism, could be an instant turn off.

Determined to stay close to the themes of nationalism and patriotism, however, I went for this equally potent and compelling clause in the National Pledge: “And Uphold her honour and glory”.

Written by the late Prof. Felicia Adebola Adedoyin and adopted in 1976 by the regime of the then Head of State, General Olusegun Obasanjo, its composer had hoped that Nigerians would strive to love and serve their country against every odd.

This headline may also not go down well with many Nigerians as ‘glory’ and ‘honour’ least describe what they feel at the moment but I’ve chosen it nonetheless as it captures the future Nigeria can achieve, albeit through more thorns and thistles. Luckily, we have enough images to validate the truism that great victories are often preceded by daunting hurdles. Some philosophy, right?

Won’t the world be a better place if being philosophical alone can actually cure all of life’s numerous troubles? Only the ‘efulefu’ would be comfortable in a fool’s paradise, I think. The sorts of existential and everyday obstacles plaguing our nation today are too real, too personal to push over to the metaphysical realm.

Last Sunday, on October 1, I had a hard time trying to convince a young man who sat next to me in church to sing the anthem and make positive pronouncements about his own country in response to the pastor’s instructions. I failed to, flatly. My promptings couldn’t be sustained for obvious reasons. He left the service before the end anyway but I could discern some of his frustrations.

Over the last few days, I’ve seen some negative headlines about Nigeria. If those were to be presented to any 63 years old man or woman as a birthday bouquet, his or her response could swing from disappointment, disillusionment, despair, even to depression. Though inanimate, the country is experiencing a flood of traumatic emotions. But one shouldn’t be surprised about the outpouring of regrets, pain, discouragement and, sometimes, hatred from the citizens.

Truly, it takes people rooted in and driven by uncommon optimism to disagree with the derisive and dismissive conclusions about this captive African and potential global giant.

It’s sometimes easy for educated or rich persons to bury themselves in the macro-economic statistics that reduce the lives of millions of people to mere figures.

One can get lost in the data churned out by Bretton Woods institutions and throw around elitist analyses that don’t reflect the day-to-day travails of most citizens. Last weekend, as I watched a middle-aged woman buy one ‘mudu’ of rice at 1500 naira at a mini-market in Abuja, something in me slumped.

She held onto her little package as if her life depended on it. I was left to imagine the number of mouths that was meant for; where the condiments would come from; and how much longer her hope for a better tomorrow could take her.

On narrating that encounter to another resident later, I was informed that that measure of rice sold for 1800 naira elsewhere in the city. Inflation that has no basis in common sense economics! See why all the talk of costs rising from, say, 20.37% to 21.24% within one year doesn’t capture the street reality in places like Nigeria?

Read Also:

My drift? At the heart of the pervasive discontent and desperation across the land is the enlarging, numbing incapacitation of the populace, most noticeable in their inability to meet the most basic of human needs.

Wants are being relegated rapidly in people’s minds. Who would tell those in positions of authority and responsibility that quality life, a given and constant factor in decent countries around the world, is no longer a primary topic among majority of Nigerians? That has since been overtaken by the meagre wish to stay alive, avoid sicknesses, not to succumb to hunger or any eventuality of mass starvation.

Add all that to the already mushrooming cocktail of a serially humiliated naira, quantum youth unemployment, largely inept political leadership, underachieving national economy, and a fast dwindling faith in a nation that was once at the top. And you instantly have a recipe for shame, the very antithesis of honour and glory.

In the face of all this festival of mediocrity and hopelessness, however, there must be some positives to pursue. From the earliest ages through the medieval era to the present time, adventure has remained a towering virtue. Adverse conditions are not always to be avoided but conquered, for they are the surest routes, though arduous, to victory and lofty rewards.

Adversity theory receives its strength from observing history about man’s capacity to invent or discover solutions to seemingly insurmountable difficulties while grappling with them. Like in childbirth, new concepts, possibilities and revived nations do emerge from gruelling situations.

Sadly, one reason many people are cynical about our prospects for corporate recovery and thriving is the blurring of lines between the often-loathed leaders on one hand and the country itself on the other.

It’s unfortunate that distinctions are not usually made between occupying political seats and the nation. The truth about the transience of the former and the perpetuity of the latter seems lost on many Nigerians as the vicissitudes confronting them bite even harder.

What’s so hard in recalling that yesterday, President Muhammadu led this country but that President Bola Tinubu is in the saddle now, for instance? As simple as that poser is, it’s in grasping its import that the love for our nation can emerge.

Although their number is ebbing, there’re millions of Nigerians alive who witnessed and benefitted from Nigeria’s period of abundance and relative sanity; when better corporate, family and individual values oiled the wheels of socio-political and economic progress. Educational institutions were true centres of learning.

Health organisations hadn’t become mere consulting clinics. Largescale hunger wasn’t a major concern. Armed robberies and other violent crimes weren’t this common. Well-paying jobs were looking for graduates and school leavers in their hundreds of thousands.

Those who schooled abroad couldn’t wait to return home to contribute to the nation’s development and earn good salaries. Embassies here had no reasons to treat visa-seeking Nigerians with open disdain as the wish to travel out was not maniacal. Travellers preferred short stays outside which, in any case, weren’t status symbols at all.

Even the “checking out” swag of the ‘Andrew’ period occasioned by the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the late 1980s and early 1990s was short-lived; at any rate not comparable to today’s ‘japa’ syndrome. And the currency notes were worth much morey than the papers that bore them.

Of course, Nigeria then was no paradise. Virtually all the evils we’re stuck with now were present but in far smaller degrees, we must agree. The point at which things started tumbling up to this current despicable level is subject to queries. Whichever way the answers go, tearing down the country at every given chance can’t be the way out.

No nation is immune from heartaches and convulsions. Only that many other people tend to display affection for their own countries no matter the circumstances. Nigerians urgently need that kind of orientation for their country to wake up again.

Ekpe, PhD, is a member of THISDAY Editorial Board.