Tale of two Nigerian elections

By Festus Eriye,

One of the big stories of the 2023 general election cycle was about how former Anambra State governor and presidential candidate of the Labour Party (LP), Peter Obi, had become a third force come to disrupt Nigeria’s cosy two party arrangement. But two elections, just three weeks apart, confirm that rumours of a revolution in our politics were grossly exaggerated.

The outcome of the February 25 presidential contest rubbished all opinion polls which predicted a sweeping victory for Obi even in the most unlikely of places.

More conservative voices had suggested that the Labour flagbearer would struggle to meet the constitutional requirement of winning twenty five percent of votes cast in 24 states given his very weak support in the North.

That turned out to be the case. However, he did exceed expectations as those who pointed at the weak structures of his party believed he would only do well in his Southeast homeland. But he broke out – winning majorities in several South-South and North-Central states.

That stronger than expected performance had Obi laying claim to the presidential prize despite the umpire confirming he came a modest third.

On the strength of the buzz generated, many awaited confirmation on March 18 during the gubernatorial polls, that he and his Obidients had come to stay as the predicted third force.

As I write this, Labour is in a desperate fight to claim Abia State. Elsewhere, including most notably Lagos, the coalition that delivered the famous February 25 upset win had scattered.

Even in his home state of Anambra where his movement was expected to punish Governor Chukwuma Soludo for having the audacity to question Obi’s bid, the ruling All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) coasted home with a comfortable majority in the House of Assembly.

So how did the Obi wave disappear in a little over a fortnight? Was this just a personality cult that took on a life of its own with blood transfusion from an ethnic group’s political aspirations? Was this just an opportunistic arrangement that took advantage of a very strange environment leading to the elections? Who goes to electoral battle by dealing the same electorate whose favour they seek with a calamitous cash crunch? Obi and Atiku Abubakar actually hailed the Central Bank’s naira confiscation gambit.

Even his popularity with young people in the run-up to the polls suggested opportunism. At 62, he was no spring chicken. But a demographic fed up with the leading parties saw in the sixty-something someone younger than the two septuagenarians heading the All Progressives Congress (APC) and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) tickets.

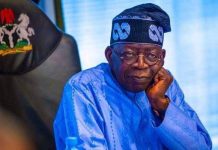

He was wildly popular with Christians because religion became a hot button issue the moment the ruling party’s Bola Tinubu made the strategic choice to run with Senator Kashim Shettima, a fellow Muslim from the northeastern Borno State. This was a risky and controversial move given that, conventionally, parties balance their tickets along religious and regional lines.

But it wasn’t an unprecedented one because in 1993, the Southern Muslim candidate of the then Social Democratic Party (SDP), Chief M. K. O. Abiola, successfully ran with Babagana Kingibe, again, from Borno State, who shared his faith.

Tinubu’s decision to travel the same route as Abiola unleashed the hounds of hell. Some of his closest Christian supporters from the North like former Speaker of the House of Representatives, Yakubu Dogara, and former Secretary to the Government of the Federation (SGF), Babachir Lawal, broke loudly and publicly with him.

The Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) and its affiliates were not far behind. Their furious reactions showed quickly that the APC candidate had a major problem on his hands.

Sensing an opening to be exploited, Obi quickly took his campaign to the church, embarking on a whistle stop tour of prominent Pentecostal congregations.

He was often welcomed with cheers that shook the rafters. On one of those occasions, he challenged the church to “take back your country.” The body language of pastors of these mega churches made it clear they were delighted with him.

Tapping into the rich vein of religiously intolerance which had built up between 1993 and 2024 would yield massive dividends for the Labour candidate as we would soon see.

The amazing thing is the other side of the faith divide didn’t take up the bait by urging their followers to ‘either take back or defend their country.’

Read Also:

Even up to the eve of the polls most political commentators were largely dismissive of Obi chances, pointing to the lack of nationwide penetration by his Labour Party. They missed how riled up the Christian population had become because of APC’s same faith ticket.

They underestimated the influence that powerful Pentecostal preachers had on their congregations – many of whom were blackmailed to toe the denominational line.

Perhaps those who came closest to identifying what was going on were a series of polls which suggested than beyond disruption, Obi would go on to win by lopsided margins.

One or two even predicted he would triumph in Lagos, Tinubu’s fortress which he has defended successfully against all forms of encroachment for over two decades. It was unthinkable and many laughed them to scorn because the pollsters mostly took limited online samples.

But on February 25, the unimaginable happened. Tinubu’s territory was breached with the unheralded Obi eking out a roughly 10,000 vote majority. That wasn’t the entire story.

A party that wasn’t expected to do well beyond the Southeast, triumphed in key South-South and Middle Belt states. In the end Labour won in 12 states just like the bigger APC and PDP.

It was a stunning performance. It was as if the end had truly come for the powers-that-be. It gave hope to Obi supporters who had celebrated the polls as evidence that their insurgency against the old political order was about to be brought to a successful conclusion.

So, while they found themselves in a disappointing third place in the presidential contest, they could console themselves with pinching Tinubu’s Lagos crown jewel as well as winning governorships in a swathe of Southeast, South-South and North-Central states.

More than that, Obi and Obi-dients who truly believed they won the presidential election had an opportunity to prove that their performance on February 25 wasn’t a fluke. Some of them urged their members to turn up in large numbers on March 18 to crush those who had “stolen their mandate.”

While many have been very generous in their plaudits for the former Anambra governor and his efforts, clearly what happened in Lagos and elsewhere must be put in proper perspective.

Everyone loves a romantic story and there was none more seductive than an unheralded billionaire figure with a reputation for frugal living taking on entrenched political forces and overthrowing them. It was a narrative that foreign correspondents lapped up and regurgitated.

Some even called the events of February 25 a revolution that was televised. March 18 would show that there was nothing revolutionary about what played out three weeks earlier. Rather, we just had affirmation that the same factors that have always driven Nigerian politics are ever so present.

I have touched on religion but ethnicity was also a powerful factor. For the first time in a long while, the candidates were from the three most populous groups in the country. It was no surprise when each did well in their home base.

Former Vice President Atiku President did extremely well in the Northeast, Tinubu performed well across the Southwest. But Obi’s performance in the Southeast was astounding.

In some states he scored more than 90% of votes cast. In modern times the only places where that used to happen was in the old Soviet Union or Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. It was all down to a region embracing one of their own.

When that factor was taken out of the equation on March 18, when the issues became local even within tribal enclaves, we had totally different outcomes.

In Imo State, where Obi won over 80% just three weeks ago, his Labour was wiped out; the ruling APC took 25 out of 27 Assembly seats. In Ebonyi, the ruling party retained the governorship comfortably.

This state is particularly interesting because while it gave Obi and Labour near total support in the presidential election, in the simultaneous National Assembly poll APC took the three senatorial seats.

Clearly, what occurred three weeks ago was just an opportunistic political foray that was going nowhere. In the end it blocked the PDP’s path back to power and helped elect Tinubu as the much-vilified Soludo had predicted.

One day is a long time in politics, three weeks a life time. The events of the last 21 days are an object lesson in the folly of drawing hasty conclusions about Nigeria’s power games.

Suffice it to say the structures Obi swore he had come to overthrow remain firmly in place. His legions have scattered in different directions. That’s another way of saying the disruption just got disrupted.